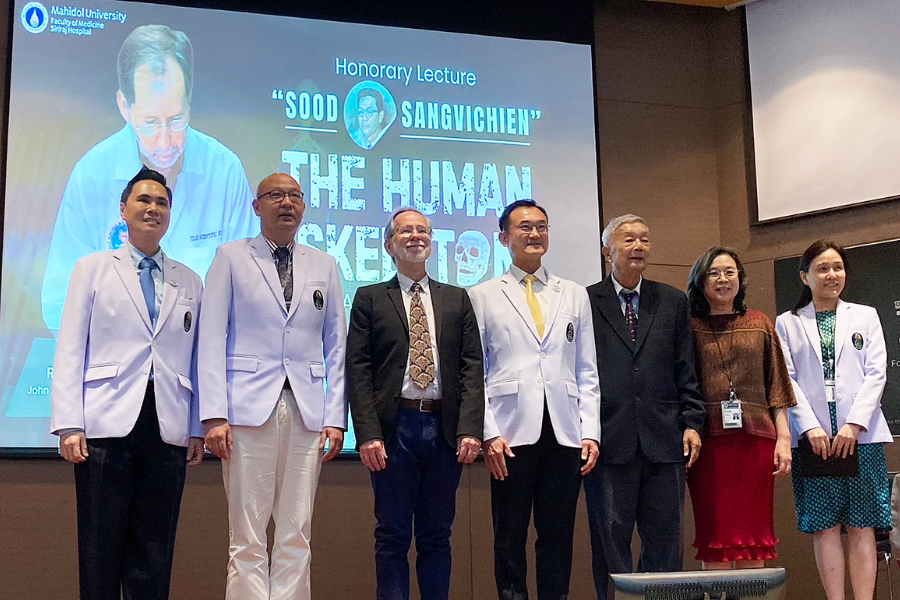

JABSOM’s Dr. Robert Mann just returned from Thailand where he accepted the Sood Sangvichian Gold Medal Award from Siriraj Hospital in Bangkok, the oldest and largest hospital in Thailand. For more than three decades, Dr. Mann has been giving forensic anthropology talks, workshops, and training “pioneer forensic osteologists,” forensic pathologists, anatomists, archaeologists and police throughout Thailand.

Q: How long have you been working in Thailand?

A: I first came to Hawaiʻi when I worked for the U.S. Government’s Central Identification Lab of Hawaiʻi (CILHI), which later became known simply as the CIL, or Central Identification Laboratory. About four months into the job, I found myself on my first mission deep in the jungles of Southeast Asia. We flew to our site in a helicopter and then had to cross a remote jungle river in Laos on a bamboo raft. It really felt like something out of an Indiana Jones movie. Teams still go into most Southeast Asian missions from the CIL through Bangkok where we have our planning meetings, and collect all of our excavation gear, supplies, and equipment to survive for several weeks at a time and then we’re on to Vietnam, Cambodia, or Laos. My first CIL mission was in 1992, and within about the first year I was asked to give a talk at the Royal Thai Air Force Base in Bangkok. I had been doing a lot of missions excavating airplane and helicopter crash sites and searching for missing soldiers from the Vietnam War. The Royal Thai Air Force was interested in learning more about what our recovery teams at the CIL did and how we did it, so I gave a presentation on skeletal trauma sustained in air crashes and what to look for. I also talked about finding airplanes. When airplanes were shot down over Southeast Asia it was like a hardware store falling out of the sky and landing in jungles, rivers, streams and near remote villages. Somebody saw it happen, went to the crash site, and they often took pieces of the airplane or the helicopter away. I've seen coffee tables made from the rotor of a Black Hawk helicopter, part of a fighter jet wing used as a washing platform along a jungle river, and a smoking pipe from an engine fitting. Pieces of the aircraft skin, you name it, are used to repair houses and anything else that the metal can be used for. My first visit was in 1992, and I did many missions over the years.

Q: Do you remember your first mission back in 1992?

A: Yes, I do. It was a big case where we were searching for the grave of an American civilian who was in an airplane that was shot down over the jungles of Laos. He was called a "kicker." The kicker was somebody who opened the back end of the aircraft and kicked rice and other provisions out of the back of the plane to fighters on the ground. The airplane was shot down, and some of the crew was taken prisoner and held in jungle prison camps. The American we were looking for had escaped with another prisoner of war (POW), and at some point, he was reportedly shot and killed by the Pathet Lao, the Communist forces. They saw him, they killed him, and then they buried who they later identified as an American, in the jungle along the river. We went to Laos to look for him and we finally found human remains. We thought we had our missing “kicker”, but it proved not to be who we thought it was. Our CIL investigative teams ran down more leads over the years and we finally identified him. The family followed the case very carefully and I met them several times, so it was a big case that’s still always with me.

Q: How often would you return to Thailand in your role with the CIL?

A: The official number that I filed when I retired after 32 years of Government service was 55 missions around the world. These were search and recovery missions in Southeast Asia, Japan, South Korea, North Korea crossing the DMZ (demilitarized zone), Okinawa, the Philippines, Saipan, Russia, Lithuania, Latvia, Belgium, Poland, and Germany. We would look for an aircraft crash site or a burial, do an excavation, and bring the remains and material evidence back to Hawaiʻi for forensic examination. In addition, I probably did another 100 or more short trips to Southeast Asia, Europe, Saudi Arabia, and Siberia to examine remains purported to be those of one or more missing American soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines.

Q: After your time at CIL, you joined JABSOM in 2014. How often do you still go to Thailand to teach?

A: I started teaching various aspects of forensic anthropology in Thailand on a regular basis nearly 30 years ago, and it all began with a phone call. Thailand didn't have forensic anthropologists, so I was talking to my wife and wanted to figure out how to connect with someone working in forensic medicine or archaeology so that I might be able to help them work cases or give them some training in forensic anthropology. I heard about Dr. Pornthip Rojanasunand, who is a forensic pathologist. I gave her a call “out of the blue” and learned that she had been trying to reach someone at the CIL for years. She said that call was a miracle, and from that point on, I started giving a lot of training over the years to the Missing Persons Identification Centre Section (MPIC) in Bangkok. I still provide them with training when I can and give talks on new methods of estimating age at death, biological sex, ancestry, stature, trauma and bone disease. I've also consulted on several cases with them over the years. While there are other forensic examiner offices and labs in Thailand, MPIC is the main center established solely for the identification of missing persons in Thailand. I train their forensic osteologists and if they have a case that is particularly difficult, they may send me photos, or when I'm there, they'll ask if I have time to look at a case. I've probably done 3 or 4 in-house training sessions and workshops in the past couple of years. The MPIC (now called MPIS) staff has a lot of experience, but when dealing with trauma to the skeleton, forensic anthropologists can bring a different skill set and a different and specialized approach to interpreting skeletal trauma. So, we're called in a lot to interpret trauma and look for evidence of how a person died, how long they've been dead, what kind of instrument might have been used to inflict the trauma, and we're usually able to help with that.

Q: As you look back on the tremendous impact you've made in Thailand, how do you think you've helped advance their forensic efforts?

A: I've taught and still teach at several universities and medical schools in Thailand such as Chiang Mai University in the north, Khon Kaen University in the northeast, and Mahidol University, Chulalongkorn University, and Siriraj Hospital in Bangkok. I was training their graduate students and sometimes undergraduates, but primarily people in medical school who would go on to be forensic osteologists, as they usually don’t get specialized training in anthropology. They may be police, medical doctors, or someone working on their master’s degree or PhD focusing on the human skeleton, much like gross or skeletal anatomy that we teach in the U.S. They don't technically have forensic anthropologists because they're not getting the anthropology training. Thailand has many skilled and very highly experienced archaeologists and bioarcheologists, and many of them recover and examine human skeletal remains, but I don’t think most of them deal with police and medical examiner cases; that’s where forensic anthropology and its specialized training comes into the picture. So, I often go to several Thai universities and show them how we do forensic anthropology and skeletal recoveries and skeletal analyses in the United States, based on U.S. standards and practices, and show them how they might apply it all in Thailand if they want to. Over the years I’ve trained undergraduates, graduate students, and post-doctoral folks with PhDs and MDs. Many of the people that I trained and mentored over the years are working in their own labs or they’ve established labs at universities, medical schools or forensic medicine labs throughout Thailand. They are often called "pioneer forensic osteologists" and are foundation and play a big role in the future of forensics in Thailand.

Q: Wow, you've been teaching the pioneers of Thailand for the last three decades, and it's culminated in this award. What are your thoughts about receiving this honor?

A: It's tremendous and I’m honored to receive the award. In the different talks that I give around the world, I always try to think of new talks and new approaches, new things to teach people and new methods. A lot of how and what I teach came out of the CIL and our JABSOM lab here at the University of Hawaiʻi. For example, in one of my talks that I call "45 Years Working with the Dead" I look back on my career from my first to my most recent case and think, ''Have I been doing this for 45 years?'' and I have. My first case was in 1978 or 79, so it's right at 45 years, and I've trained many people around the world and am still training people here in Hawaiʻi and at universities in Southeast Asia, Europe and even South Africa. I never thought I'd be teaching at a university. When I was younger, I wasn't crazy about going to school, but things really kicked off when I was exposed to a class in bones, forensic anthropology and archaeology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. I couldn't get enough of bones and learning about them, and that’s where I am today…I’m still falling into “rabbit holes” and exploring new topics daily. What I'm able to do is take all these trips that I've done, all the missions I've done for the government and all the skeletal cases that I've examined while at the Smithsonian Institution, and I'm able to pull all of these different specialties and “lessons” together. I'm able to pull together and teach such topics as time since death, bone disease, skeletal trauma and what happens to a human body after death to a deep level. I use ancestry and how to determine the biological profile, pull them all together in one person, and then train folks who then go out and train others. So, I really am training the trainers, as they say. To me, it's a remarkable honor to get this award and it reminds me that forensic anthropology is an offshoot of medicine. Hundreds of years ago, medical doctors looked at skeletons to determine age, ancestry, sex, stature, and other things and some started calling themselves anthropologists, so they combined medicine and anthropology. Here I am a few centuries later going from anthropology in reverse to medicine, and we're reversing the role, but it's really all intertwined. I'm very grateful to get an award like this from a prestigious hospital and it helps strengthen and spread the word about the role and importance of forensic anthropology not only in Thailand, but worldwide.

Q: Do you feel like you have a responsibility to share your knowledge with the world?

A: Yes, I do. If I had to guess, I've looked at many thousands of skeletons, and as you learn, you get better at what you do, your skills get better, you can see further, and you can see deeper and clearer. I'm really fortunate. Actually, I would do this for free because I think that forensic anthropology owes a responsibility to the community, and to be clear, the community is not just outside our door here in Kakaʻako, not just the state of Hawaiʻi and not just the United States. It's around the world. So, if we can help people solve cases and bring home the dead and the missing, in the many roles that forensic anthropology can play, I think we absolutely owe a debt that we have to pay for that. It's such an important role that we play as forensic anthropologists in medicine and in medical-legal cases.

Q: You've been involved in many big cases, some of which couldn't be solved without the expertise of a forensic anthropologist. Do any stick out to you?

A: Some of the biggest forensic cases to make the news worldwide have had one or more forensic anthropologists on the teams that examined them. I, for example, examined some of the victims of 9/11, victims of serial killers Jeffrey Dahmer and Kendall Francois, helped establish the identity of the Vietnam Tomb of the Unknown Soldier buried in Arlington National Cemetery, examined the remains of War of 1812 soldiers, and the sailors who died aboard the USS Monitor and the CSS Hunley ships from the American Civil War. On my recent trip to Thailand, I examined some of the unidentified victims’ remains of what’s been called the “Thai Ted Bundy” in Bangkok. I think forensic anthropologists play a critical role and a unique role because there's nobody else out there with our specialized skill sets to examine human remains the way we do. You have to really know the human skeleton to the nth degree because there's so much human variation and so much detail that you have to not only look for, but have to be able to correctly identify. You have to be able to look at a bone or a complete skeleton and say, this is normal; this is not normal. If it's not normal, what is it and what caused it? Is this something that resulted in a person's death? Did it lead up to their death? Was it related to their death? Or did it have nothing to do with their death at all?

Q: You've worked on some of the biggest global cases over the years, and you've brought that personal knowledge to Thailand. When you accept this award, will you be sharing new knowledge about bringing these cases to court?

A: Yes, I've shared a lot about my work as a forensic anthropologist, but there’s always something new to teach and to learn, as both are usually a two-way street. I have yet to fully share how to put the details of a skeletal examination and findings into a comprehensive written forensic anthropology report (FAR). It's an important part of the job because our report may go to court, so one of my new talks in Thailand covered the specifics of how to write an effective and comprehensive FAR. My focus was to show how to systematically format and write a forensic report in a way that reflects standard medico-legal practices and procedures and that can be understood by police, the court, the medical examiner, the family, and other scientists. “Doing” forensic anthropology is only one step of many in finding, recovering and identifying human remains and “reporting and supporting” your findings and conclusions in a court of law or to a family may be the last step in the process.