Renowned forensic anthropologist Dr. Robert Mann, Professor of Anatomy and Pathology at the John A. Burns School of Medicine, was sent to Maui to aid in the identification efforts of the victims in the deadliest U.S. wildfire in more than a century.

“It was unlike anything I really expected,” he said.

As of this date, 115 died in the Maui wildfires, and 800-1,000 people remain missing. State officials called on Dr. Mann for his vast experience in helping families identify loved ones in some of the world’s largest disasters and tragedies. As a forensic anthropologist, he helped identify the remains of victims from 9/11, the Indian Ocean tsunami, and multiple plane crashes.

“Even with all the mass disasters I’ve done and all, every single one of them is different. The Maui wildfire disaster certainly was different,” he said.

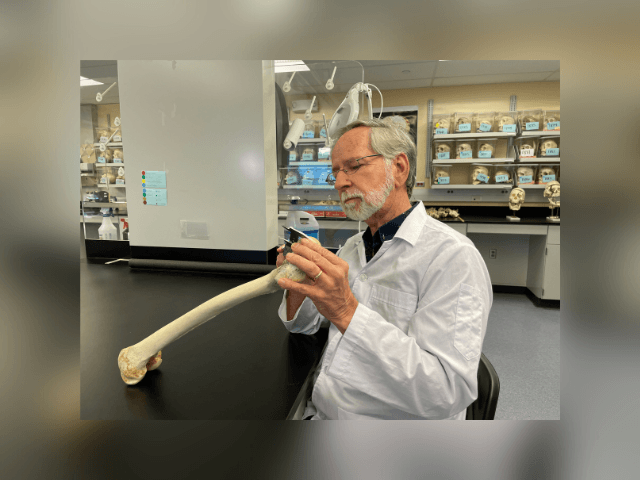

As a forensic anthropologist, Dr. Mann uses bones and bone fragments to help identify remains. The disaster on Maui is proving difficult. According to Maui County, the scope of the disaster scene in Lāhainā is 2,170 acres. Dr. Mann said the temperatures from the inferno and the gusts from Hurricane Dora also pose challenges in the recovery and identification effort.

“This is not an airplane crash where you’ve got 20 people that are manifested on the airplane. This is a huge area, and the perimeters are extremely big,” Dr. Mann said. “One of the complicating factors would be the high winds. Those winds will move things that were at one point here and then end up being a hundred feet away.”

A team of forensic pathologists, forensic anthropologists, dentists, radiologists, fingerprint technicians, DNA specialists, firefighters, police and FBI agents were all sent to aid in the recovery and identification efforts. While others were sifting through the disaster site looking for remains, Dr. Mann was one of three forensic anthropologists at the morgue, working with located remains, trying to make the connections to the identities that loved ones are desperately seeking.

“Forensic pathologists are not trained to identify bone fragments or tell you anything about it,” Dr. Mann said. “We will pick the bones up and offer insight. We can tell if something is a right ulna or a left leg. This can then lead to identifying the age or biological sex of a victim. So although the dentists do the teeth, we do the bones, and the pathologists do the bodies, we work as a team.”

Because of the sheer size of the disaster scene, Dr. Mann knows it may take years for some identities to be known. He says 9-11 victims are still being identified more than 20 years later.

“Others may need to be identified by DNA. Some of the badly burned remains are not going to yield DNA, but some of them will,” he said.

As the recovery and identification efforts may span years, Dr. Mann asks for patience.

“I see the process continuing, and it’s not an easy process,” Dr. Mann said. “Nobody’s enjoying this, but there’s no other way that I know of to do it. It’s one step at a time, and you’re climbing this very tall ladder where the only way to get to the top, which will be the identification, will be one step at a time.”

Dr. Mann has worked at JABSOM for the last eight years and has called Hawaiʻi home since the 90s, so there’s an added reverence he has when assisting on Maui.

“This is in our own backyard,” he said. “This is home for many of the people who are working this. You run into people at the scene who lost somebody, and it’s a very personal thing for them. It becomes very personal for those of us working with them. Because this is in our own backyard, we want to do it right, and we’re going to do our best to continue to do the right thing.”

Dr. Mann’s osteology and forensic anthropology lab at JABSOM is the only one of its kind in the state. It assists in mass disasters like what we’re seeing on Maui, but it also educates doctors in bones and bone disease and trauma.

“Hawaiʻi hadn’t had this kind of a lab until now,” Dr. Mann said. “So this is Hawaiʻi’s lab, and I hope every state in the United States has a forensic lab like this. I think we’re doing our best, and I think we’re getting to be a gold standard for the way skeletal labs are structured.”